What is Cerebral Cortex

The cerebral cortex is the outer layer of neural tissue covering the cerebrum. Thickness varies between 1.5 and 4.5 millimeters depending on the region. Motor cortex tends toward the thicker end. The calcarine sulcus, where primary visual cortex sits, runs thinner.

Gross Anatomy

The cortex folds into gyri and sulci. Total surface area in humans averages around 2,500 square centimeters. Zilles and Amunts published updated measurements in 2010 using high-resolution MRI, and their figures have held up reasonably well. The folding pattern is not random. Primary folds appear consistently across individuals. Secondary and tertiary folds show more variation.

Four lobes divide the cortex: frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital. The boundaries are somewhat arbitrary. The central sulcus separates frontal from parietal. The lateral sulcus marks the superior border of the temporal lobe. The parieto-occipital sulcus is visible on the medial surface.

Four Lobes of the Cortex

- Frontal — Executive function, motor control

- Parietal — Sensory integration, spatial awareness

- Temporal — Auditory processing, memory

- Occipital — Visual processing

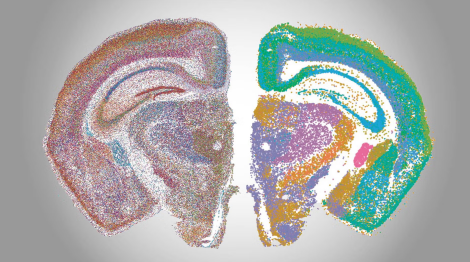

Cytoarchitecture

Brodmann published his cortical maps in 1909. He identified 52 distinct areas based on cellular organization. The numbering system is not intuitive. Area 17 is primary visual cortex. Area 4 is primary motor. Area 44 and 45 together form Broca's region.

Von Economo and Koskinas produced a more detailed atlas in 1925. Their work included cell density measurements that Brodmann had not attempted. Modern researchers still reference both atlases, though MRI-based parcellations have largely taken over for in-vivo studies.

The cortex organizes into six layers, numbered I through VI from surface to white matter. Layer IV receives thalamic input. Layer V contains the large pyramidal cells that project to subcortical structures. Layer VI sends feedback to thalamus.

Not all cortex has six clear layers. Primary motor cortex lacks a distinct layer IV. The term "agranular cortex" describes these regions. Primary sensory areas have a prominent layer IV and are called "granular" or "koniocortex."

| Layer | Primary Cell Types | Main Connections |

|---|---|---|

| I | Few neurons, mostly dendrites | Local processing |

| II | Small pyramidal cells | Cortico-cortical |

| III | Medium pyramidal cells | Cortico-cortical output |

| IV | Stellate cells | Thalamic input |

| V | Large pyramidal cells | Subcortical output |

| VI | Heterogeneous | Thalamocortical feedback |

Functional Organization

Primary sensory and motor areas occupy specific cortical territories. Primary visual cortex sits in the calcarine sulcus. Primary auditory cortex lies in the superior temporal gyrus, buried in Heschl's gyrus. Primary somatosensory cortex runs along the postcentral gyrus.

Penfield's stimulation studies from the 1930s through 1950s mapped the motor and sensory homunculi. The maps are distorted. Hand and face representations take up disproportionate cortical territory. The trunk and proximal limbs get relatively little space.

Association cortex fills the remaining territory. Posterior parietal cortex integrates sensory information. Prefrontal cortex handles executive functions. Temporal association areas process object recognition and semantic memory.

Cortical Columns

Mountcastle proposed the columnar organization hypothesis in 1957. He found that neurons along a vertical penetration through somatosensory cortex shared receptive field properties. Hubel and Wiesel extended this to visual cortex in the 1960s. Their orientation columns became textbook material.

The columnar model has taken criticism over the years. Horton and Adams published a skeptical review in 2005. Columns are clearly present in some areas and some species. Their universality as a computational unit remains debated.

Minicolumns

Minicolumns are narrower structures, roughly 50 micrometers wide. They contain around 80 to 100 neurons. Casanova has argued that minicolumn abnormalities appear in autism and schizophrenia. The evidence is mixed. His 2002 paper on autism generated a lot of follow-up studies with inconsistent results.

Development

The cortex develops from the telencephalic vesicle. Neural progenitors in the ventricular zone divide and produce neurons that migrate outward. Radial glial cells provide scaffolding for this migration.

Layer VI neurons are born first. Subsequent layers form in an inside-out pattern. Later-born neurons migrate past earlier-born neurons to reach more superficial layers. Reelin signaling guides this process. Reeler mutant mice, which lack functional Reelin, show inverted cortical layering.

Cortical folding begins around gestational week 20 in humans. The mechanism is not fully understood. Van Essen proposed in 1997 that axon tension drives folding. Richman and colleagues had earlier suggested differential growth rates between inner and outer cortical layers. Both factors probably contribute.

Connectivity

Cortical neurons form approximately 150 trillion synapses. Most connections are local. Long-range cortico-cortical connections travel through white matter bundles. The corpus callosum contains roughly 200 million axons connecting the hemispheres.

Feedforward and feedback connections have different laminar patterns. Feedforward projections originate in superficial layers and terminate in layer IV. Feedback projections originate in deep layers and avoid layer IV. Felleman and Van Essen catalogued these patterns for visual cortex in 1991. Their hierarchy model influenced two decades of vision research.

Thalamocortical connections deliver sensory input. Each sensory modality has a dedicated thalamic nucleus. The lateral geniculate nucleus projects to visual cortex. The medial geniculate goes to auditory cortex. The ventral posterior nucleus serves somatosensory.

Thalamocortical Pathways

- Lateral Geniculate → Visual Cortex

- Medial Geniculate → Auditory Cortex

- Ventral Posterior → Somatosensory

- Corpus Callosum — 200M axons

Clinical Relevance

Cortical lesions produce deficits that map onto functional anatomy. Left frontal damage near Broca's area causes expressive aphasia. Left temporal damage to Wernicke's area causes receptive aphasia. Right parietal lesions can produce hemispatial neglect.

Stroke remains the most common cause of focal cortical damage. Middle cerebral artery occlusion affects lateral frontal and parietal cortex. Posterior cerebral artery stroke damages occipital cortex and can cause cortical blindness.

Neurodegenerative diseases show regional predilections. Alzheimer's disease begins in entorhinal cortex and hippocampus before spreading to association cortex. Frontotemporal dementia targets frontal and anterior temporal regions. Primary progressive aphasia variants affect left perisylvian cortex.

Current Research Directions

Large-scale connectomics projects are mapping cortical wiring at synaptic resolution. The Allen Institute has published mouse cortical connectomes. Human data at that resolution does not exist yet. The technical challenges are substantial. A cubic millimeter of cortex contains roughly 50,000 neurons and hundreds of millions of synapses.

Single-cell RNA sequencing has identified dozens of transcriptomically distinct cell types in cortex. The BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network published a major dataset in 2023. Traditional classification schemes based on morphology and electrophysiology map imperfectly onto molecular types. Reconciling these classification systems is ongoing work.

Brain-computer interfaces are targeting cortical signals for motor control and communication. The Blackrock array has been used in human studies since the mid-2000s. Newer high-density electrode arrays from Neuralink and Paradromics aim to record from thousands of neurons simultaneously. Long-term stability remains a problem. Signal quality degrades over months as glial scarring develops.

Cortical organoids grown from stem cells now show some layered structure. They lack vascular input and do not develop normal folding. Whether they model cortical disease meaningfully is contested. A 2019 paper claiming organized electrical activity in organoids got significant pushback.

I will update this article as new data comes in. The field moves quickly. If anyone has access to recent single-cell datasets from human surgical tissue, I am interested in collaborating. My email is on the contact page.